Why you’re wrong about watches being the only male jewellery

Buffy AcaciaIt’s a sentiment we see over and over again. Whenever the gender imbalance of luxury watch enthusiasts is brought up, the instant defence is to claim that wristwatches are the only jewellery that men are allowed to wear. Of course, they will all agree that it’s not a literal imposition, but rather societal expectations which have led to these circumstances. Well, not only are they incorrect on a vast historical front, but in all modern senses too.

Let’s start with a little context and work our way forward. The concept of wearing jewellery is so old that the earliest known examples aren’t even attributed to Homo sapiens, but rather Neanderthals over 100,000 years ago. All sorts of jewellery have been worn by all genders throughout all cultures – from the elaborate, gemstone-laden pectoral jewellery of Egyptian pharaohs to the simple twisted torcs of the Celts and Norse Vikings. In Renaissance Europe, men wore far more jewellery than women. Their collections of rings, earrings, necklaces, and brooches were the same status symbols that all jewellery had been for thousands of years. So, where did jewellery’s associations of femininity and emasculation come from?

The first whispers of change originated primarily from France during the Age of Enlightenment and in post-revolutionary Paris. However, it was not originally a gendered issue. Fashion trended towards utility rather than ostentatiousness, simply because anyone associated with too much wealth would be at risk of beheading. In Victorian England, emotional repression and moral panic reached their peak, and homosexual acts were criminalised for the first time. This did spread more widely across Europe, too, and was exacerbated by the Industrial Revolution’s effects on class dynamics. With more and more men working with heavy machinery in hazardous factories, jewellery was not only less practical to wear, but harder to afford. Working class women’s jobs tended to be more sedentary, so they weren’t as likely to lose a body part in an industrial accident because of caught jewellery. In the upper classes, men’s fashion also became simpler with the standardisation of the three-piece suit, while women’s clothing allowed for more creativity.

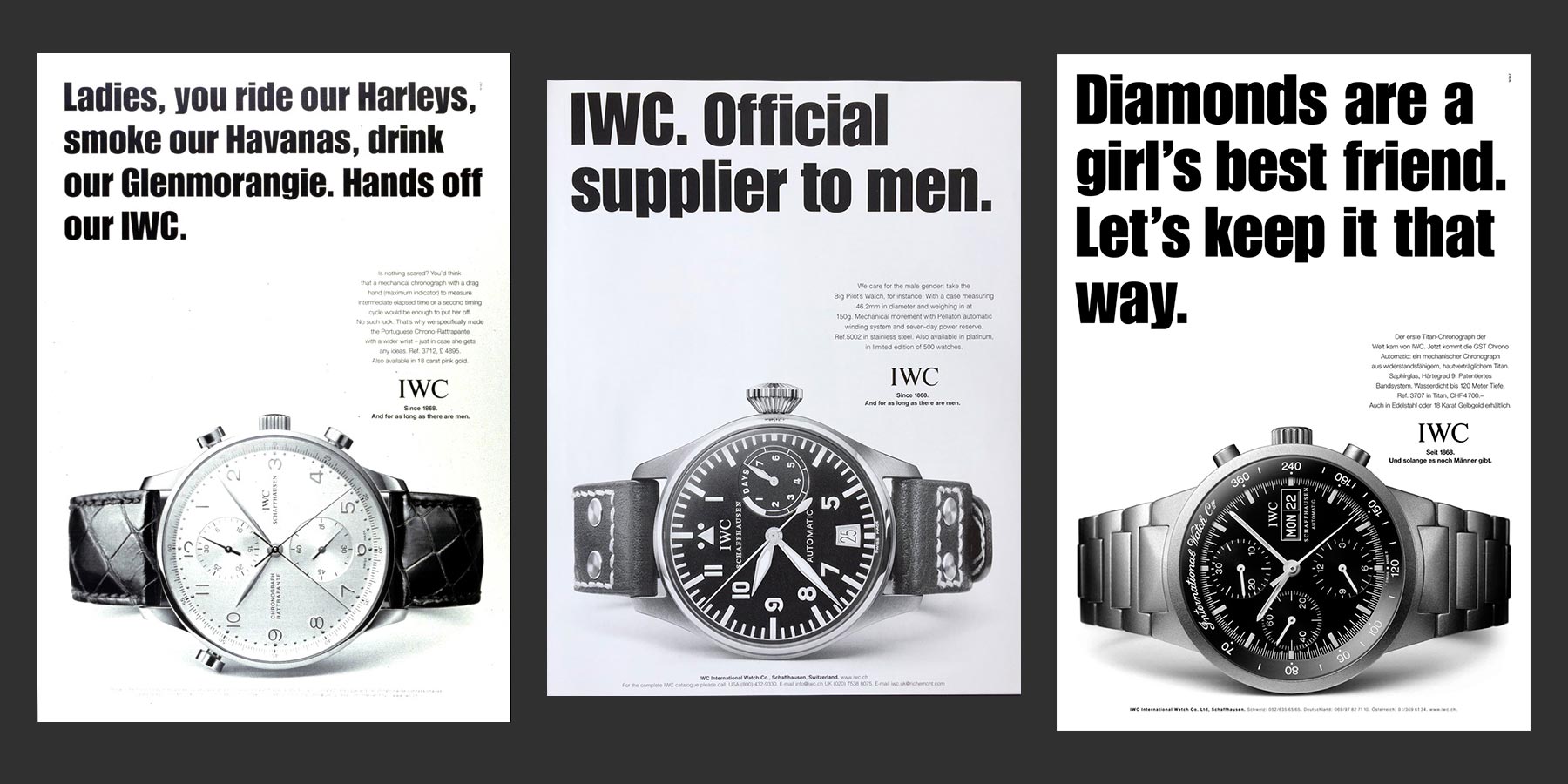

The first half of the 20th century cemented the Western world’s commitment to gendered jewellery, partly because of the number of men who fought in both World Wars, but also because of the rise of targeted advertising as a science. Roles were being presented based on idealised caricatures, such as the professional father who knows how to fix a car, and the dutiful housewife who loves to look good for her man. That cultural shift wasn’t solely an attempt to sell more products, but it didn’t hurt that the world saw a rise in brand power and department stores, rather than the craftspeople and family businesses that had previously sold or even traded directly to their local communities. That public emphasis of the nuclear family led to increased scrutiny on men’s behaviour and self-expression, dosed with enough misogyny and homophobia to shame them away from wearing the same fashions worn by women.

Despite all this, male jewellery never actually disappeared. Most people with free will get to choose their own styles, and there have always been men who wear jewellery in even the most conservative environments. Consider also that cufflinks, belt buckles, and glasses are just as jewellery-adjacent as wristwatches, and other adornments like hats can fit the same role as self-expressive status symbols. If someone walks in wearing an Akubra Rough Rider, you already know something about them, just as you can infer information from a recognisable watch. Between those items which are deemed acceptable in areas of business and all the other jewellery men are still free to wear, the options stretch far beyond wristwatches. If you feel otherwise trapped, perhaps you need to examine your own comfort levels or your environment, and realise that negative remarks on men’s jewellery are exceedingly rare outside of internet comments.

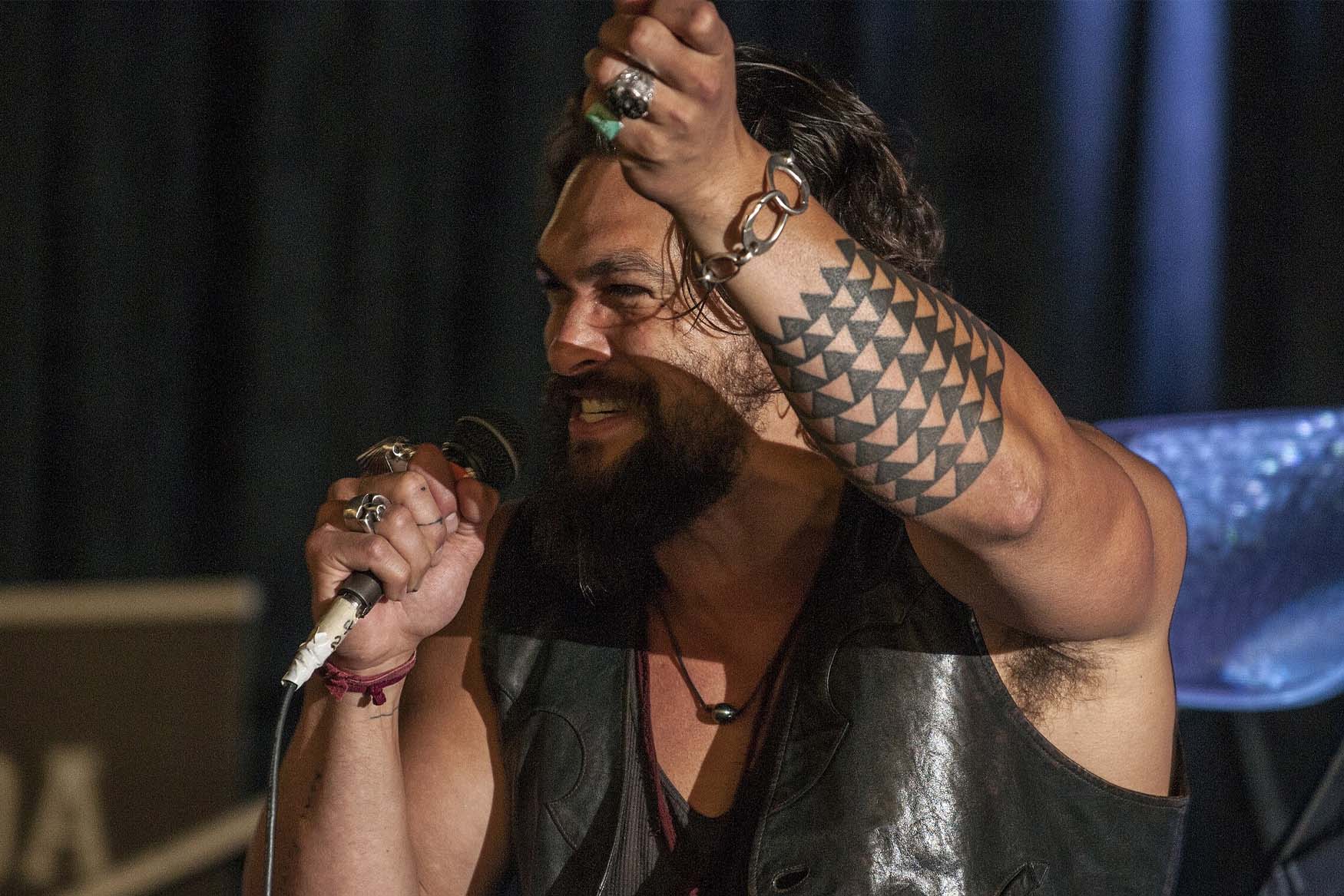

In fact, you could argue that the popularity of male jewellery is at its peak within the last century. Looking at the Oscars in recent years, we saw the likes of Cillian Murphy, Robert Downey Jr, Jeff Goldblum, Colman Domingo, Kieran Culkin, and Adrien Brody wearing elaborate brooches encrusted with precious stones. A red carpet event may not be representative of most masculine culture, but it does trickle down. We’ve already seen a huge increase in the number of men wearing jewellery comfortably on the street since the 1970s, starting with simple curb chains as necklaces and bracelets, and now evolving into pearl necklaces and earrings. If you feel that the old-fashioned nature of the watch world is exempt from this, consider the skyrocketing popularity of integrated bracelet watches and how they wear very similarly to cuff-style bracelets.

If nothing else, this is a call to pay more attention to the world around you. With open eyes, you may spot more men than you’d expect with rings, fine chains, piercings, and pendants on proud display. It’s not that the rules don’t apply to them, but rather that there are no real rules in the first place. Take things slow if you need, but experiment, wear what you like, and you’ll absolutely be happier with the results.