Everything you need to know about gold watches

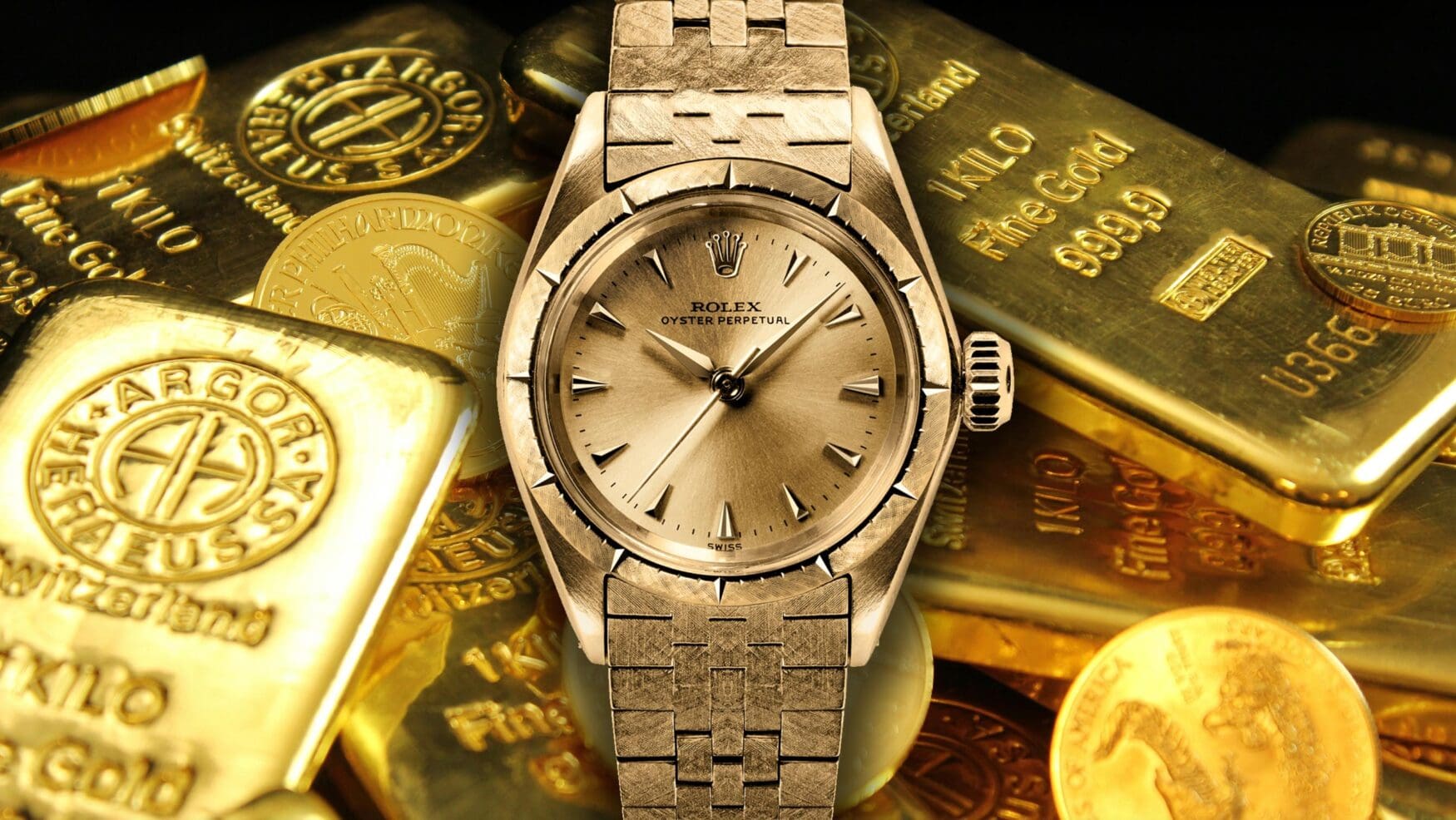

Jamie WeissAt times it feels like knowledge of gold is something we’re born with. It has been an essential part of human history for thousands of years, through trading, art, science, and even modern technology. From that first glimpse of the lustrous yellow metal, we can feel its significance in our core. But even though we understand innately that gold is valuable, there are a lot of factors to consider when you’re faced with a gold watch.

Humanity’s history with gold is always going to be slightly blurry because systems of trading have existed for much longer than written language. However, the earliest gold artefacts were found in Bulgaria, dating back to 4600-4200 BC. As a form of currency, there aren’t many other natural resources that can compete with gold: it’s rare enough that you can’t just walk outside and find some for free, but it’s not so difficult to source and refine that it’s prohibitively expensive. For a metal, it’s quite soft and malleable, which makes striking coins and jewellery fairly easy. It’s the second-least reactive element of all metals, just above platinum, which means that it’s unlikely to degrade over time, whether or not it’s being handled or in storage.

Gold purity and why it’s important

When a metal becomes valuable like gold has, the importance of purity can’t be overstated. After all, people paying for a bar of gold wouldn’t want to be inadvertently paying for other undisclosed metals. Pure gold is known as gold bullion, which guarantees a purity of at least 99.5%. When it’s turned into jewellery, however – such as a watch case or bracelet – pure gold is far too soft to be practical. It wouldn’t exactly crumble in your hand, but it would pick up scratches and lose its shape fairly quickly. For this reason, gold is mixed with other metals to create an alloy strong enough for wear and tear. Lower purities are denoted in karats, on a sliding scale with 24 karat representing pure gold. For example, 12 karat gold would be equal to 50% gold content, and 18 karat is 75%.

The most common purities of gold used in watchmaking are 9, 14, and 18 karat. Hallmarks can be stamped into the metal to help you identify it, either noting the karat directly, or a number linked to the purity percentage. A 9-karat watch may be marked with 375 to represent a 37.5% gold weight, 585 for 14 karat, or 750 for 18 karat.

There’s a common misconception that hardness, and therefore scratch resistance, increases when there is less gold content. That isn’t expressly true, because it mostly depends on which metals are being used to create the alloy. When a manufacturer is producing 9k gold, they’re mostly going to use cheaper metals like copper instead of something like palladium. The hardness of 9k gold is between 80-120 on the Vickers scale, while 18k is a fair bit harder at 135-165. 14 karat wins out in terms of hardness, which can go all the way from 140-230 depending on the alloy.

Gold alloys

The other benefit of alloying gold is that you have control over the final colour of the product. Yellow gold is, of course, the most iconic, and most alloys do try to capture the lustre of pure gold. Metallurgy in the last 200 years has popularised other tones, though, such as rose gold with its pinkish, coppery hue; and white gold, which can range from a super-pale yellow to a white which could be easily mistaken for steel or platinum. 9k gold is generally the most versatile because almost two-thirds of it is made up of other metals, but even 18k can be made to look completely white. Aside from the benefits of stealth and security that white gold provides, it’s also generally harder and more scratch-resistant than yellow or rose gold.

Rarer colours of gold have been produced in jewellery, but have not yet made it to watchmaking. Green gold, also known as electrum, is an 18-karat alloy of gold and silver with ancient roots. With trace amounts of copper and cadmium, incredible dark greens can be achieved. Purple gold is also beautiful, although technically it’s an intermetallic compound and not an alloy for various complex reasons. Hopefully, an adventurous watch brand will make some of these unusual materials into watch cases in the near future, but for now, it’s just good to know how versatile gold can be when it’s mixed with other metals.

Gold plating versus solid gold

So far, we’ve been covering solid gold alloys. However, the vast majority of gold watches aren’t actually made from solid gold, so you need to be familiar with the different kinds of coatings and platings. Not every gold-plated case is trying to fool you into thinking that it’s solid gold, and gold plating has even been around as an affordable gold alternative since the Victorian era in the 1800s.

Essentially, gold plating deposits a very thin layer of gold on top of a base metal, usually brass or steel. The plating is usually around 20 microns thick, which should last a few years before high-wear areas may start to rub through and reveal the metal beneath. A step up from gold plating is known as rolled gold, gold-capped, or gold-filled. They’re all variations on a thicker gold coating, usually up to 120 microns thick. This was an especially popular technique in the ‘40s, ’50s and ‘60s, and they generally lasted for about 10 years before wear started to show.

For modern watches and standards of quality, gold plating isn’t considered to be durable enough. Metallic gold colours are now much more likely to be achieved with a PVD coating, also known as IP or ion plating. PVD, or physical vapour deposition, is done in a vacuum. The gold material is vaporised at a high heat and then bonded to the watch case on a molecular level with electric charges. The finished product can last a lifetime, as long as it isn’t scratched up too harshly. That said, a PVD coating is always going to be more scratch resistant than any solid gold, with a Vickers hardness range of 1,500-4,500. For comparison, even 316L stainless steel has a hardness of about 140-240 Vickers.

Identifying the different types of gold in watches

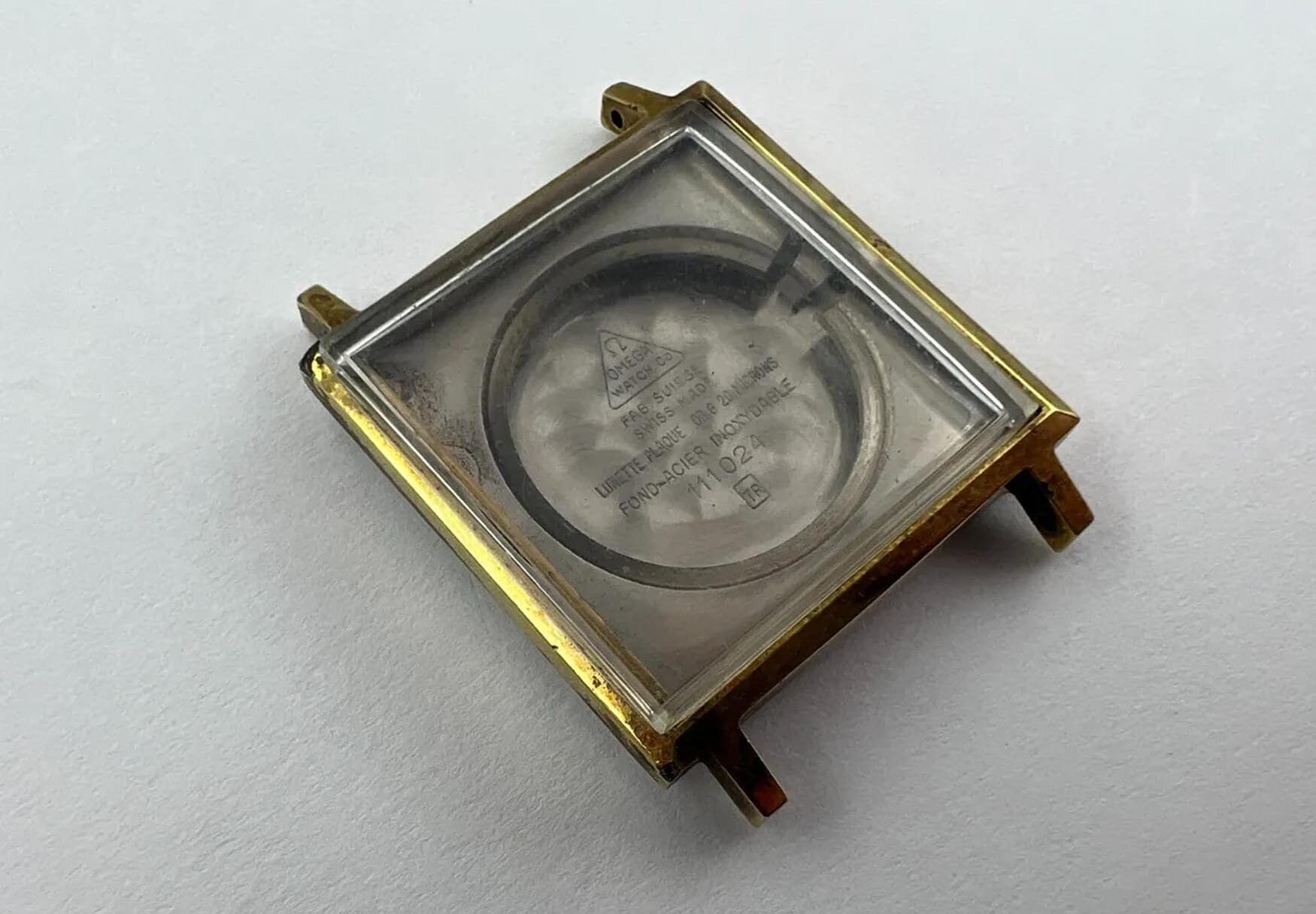

Now that you’re familiar with the main varieties of gold watches, let’s discuss how you can tell them apart in a pinch. In most scenarios, there will be plenty of clues. The vast majority of gold-plated watches have plain, stainless steel casebacks. It’s just another way of cutting costs, and it doesn’t affect how the watch looks while you’re wearing it. If the case is slightly fancier and gold-filled, then the caseback may be coated as well. Even then, a lot of watches will have clear markings or hallmarks to say what they’re made from. Sometimes they may be shortened to something like 14GF, which you can decode as being 14k gold filled.

If the case is solid gold, it will likely have a stamp that only tells you the karat purity. Some cases are a little bit sneakier, using multiple small hallmarks which you’ll need to add up. It might have a 750 to denote 18 karat purity, and nearby have a 20µ which symbolises the 20 micron thickness of the gold plating. If you’re still in doubt or there are no markings whatsoever on the case, you’ll have to open the watch up. Our former contributor Buffy found a Universal Genève watch for just A$7 at an op shop, and had no idea it was made from solid 18k gold until they opened it up and saw the hallmarks. Not many brands conceal their stamps in this manner, but it’s more common among vintage ladies’ watches.

If you can’t open the case up, for example when you’re in a store without any tools, then there is a bit of guesswork involved. What sort of tone does the gold have? If it looks too yellow or greenish, that can be a sign it’s just a plated base metal. Can you see any spots of wear? The point where the lugs meet the strap or the side of the case near the crown are always great places to check for plating being worn away. If the watch is heavily scratched but still shows no base metal, then that’s a good sign it’s solid gold.

With all of this knowledge, you’ll be a gold hunter in no time. Knowledge of Swiss watch brands will also help greatly in this area, and you’ll pretty quickly figure out which brands are likely to have made solid gold watches.

Brand-specific alloys

It’s also worth quickly discussing how some watchmakers tout the use of proprietary gold alloys, even giving them exciting-sounding names. Most notable watchmakers will all have their own proprietary ‘blends’ of gold, which will vary subtly in their composition – a little more nickel, a little more silver – but some are more substantially different than others. I’ll list a few of them here.

Last year, Audemars Piguet debuted a striking new alloy that they call “sand gold”. Somewhere between white and rose gold, AP’s sand gold is an 18-carat gold alloy with high levels of copper and palladium, which features a warm, dusty look that’s quite unlike most alloys. As of publishing, it’s only been used in four watches: two Royal Oaks, a Code 11.59 and the striking [RE]Master 02.

Omega is known for touting multiple proprietary gold alloys, including Moonshine, Canopus and Sedna Gold, while fellow Swatch Group brand Breguet has just debuted its own proprietary alloy, simply named Breguet gold. Making its debut in the case of the Breguet Classique Souscription 2025, it’s a mixture of 75% gold and 25% copper, silver, and palladium with a subtly warm yellow gold that looks very handsome in the metal.

Another Swatch Group-wide alloy that’s particularly unusual is Bronze Gold. Utilised by Blancpain and Omega to date, Bronze Gold is a bronze alloy that is enriched with 37.5% gold along with undisclosed amounts of palladium and silver (but is largely precious) which is hallmarked as 9k. The result is a bronze and gold hybrid that has a soft pink hue but is also very stable and corrosion-resistant. Is it gold? Is it bronze? Hard to say, but it’s worth discussing.

I’ve saved the most interesting one for last. Hublot’s Magic Gold is an impressive but often-misunderstood form of gold that claims to be totally scratch-resistant – and having put it to the test myself at Hublot’s manufacture, I can vouch for its indestructibility. It’s created by impregnating boron carbide ceramic with 24k gold under high pressure and temperature, with the gold filling the porous boron carbide to create a sort of alloy. While it lacks some of the sheen of other gold alloys, its scratch-resistance makes it more robust than any other gold watch.